Some of you may recall the South Korean app Zepeto that went viral among Gen Z users a year and a half ago. The app, which renders selfies into animated avatars and lets people adorn their computer-generated manifestations with virtual items, appears to have sustained its relevance. It has amassed 150 million registered users, the company told TechCrunch recently, although its number of monthly active users, which is a better metric to gauge an app’s performance, hovers around 10 million.

China is by far the largest market for Zepeto, locally known as Zaizai (崽崽), an affectionate nickname for children. “Zaizai aspires to develop into a comprehensive ecosystem while also offering robust content across China,” affirmed CEO Daewook Kim.

The app could benefit from its pedigreed background. It’s developed by the selfie app Snow, of which parent company Naver also owns the Asian messaging giant Line.

It’s not uncommon for a popular photo-editing tool to fade out as people move onto the next trending alternative, either because the new player arrives with more impressive visual capabilities or its marketing stunt creates a spell on many — or both. As such, apps that are disposable and serve utility purposes often have to think hard about retaining their users or engage aggressively to monetize them while the going is still good.

Zepeto did both.

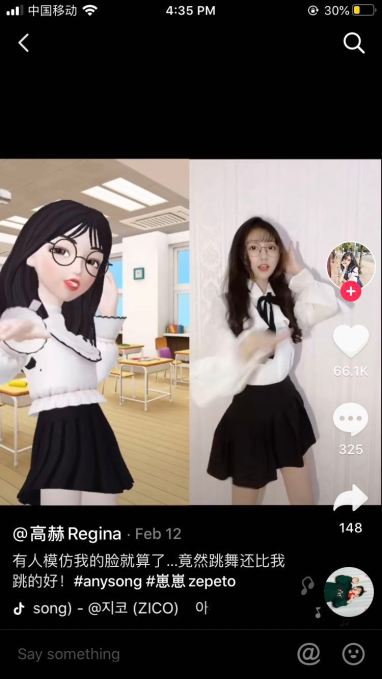

Screenshot: a user shares videos of herself dancing and her Zepeto character dancing on Douyin

The app includes a social networking function where users can interact anonymously through their avatars in virtual spaces akin to The Sims. The challenge with that, of course, is building a big enough network that lures people to keep returning.

Zepeto also comprises of a series of mini games that are evocative of what Lee described as peaceful exploration people are enjoying in red-hot Animal Crossing.

In other words, the business is ripe for selling virtual items. Indeed, the leader in this category of business, Tencent, once generated the bulk of its income from the items it sold to decorate users’ virtual profiles and spaces, a business modeled on the South Korean internet pioneer Cyworld. That was before Tencent earned a wider global reputation by building WeChat and operating blockbuster video games.

Zepeto has so far generated some $10 million from 600 million pieces of virtual items sold. It stepped up the effort recently by launching a creative marketplace where third-party artists can offer their virtual lines of clothes and accessories. Called Zepeto Studio, the store clocked around $700,000 in sales in its first month. Many add-ons are branded — a common strategy for photo-enhancement apps — so you can sport things like virtual Nike apparel.

“We’ve partnered with global brands like Disney and Nike, as well as celebrities like BTS. We hope to continue to bring exciting partnerships to Zaizai Studio as well as better service to our creators,” said Rudy Lee, head of Zepeto’s global business, adding that the Studio feature for China is scheduled to launch mid-May.

Branded Nike apparel on Zepeto

If enough people keep using Zepeto, the third-party store can be a lucrative pursuit for designers. Among Zepeto’s 60,000 registered artists, the highest-paid creator pocketed some $9,000 in sales in the first month.

But as numbers grow, Zepeto is also getting cautious about keeping its marketplace civil. The firm maintains an internal moderation team that weeds out “political messaging, hate speech, or discriminatory messaging on the virtual clothes,” said Lee. The rule is particularly pertinent to its development in China where the flow of information is strictly controlled.

Another way to survive as a utility tool is to piggyback off another app’s success. We have written about the way PicsArt, a photo-editing app that rivals VSCO, managed to stay in the game by supporting TikTok-inspired stickers. Zepeto has taken notice. Many of its users are now sharing their animated avatars on Douyin, the Chinese edition of TikTok, observed Lee.